Do you know your vinyl records contain more than just music?

When I was a newbie in the vinyl world, I was curious to learn how a vinyl record works, which took me a while to figure everything out.

After which, I was just becoming confident that I knew everything about vinyl records, and one day, someone introduced me to the ungrooved part of a vinyl record.

He showed me some etchings and codes on dead wax that I never knew about, and all I could say to you myself is there is still a lot to learn.

Just like me, many people still ignore the dead wax and rely on the record label and jackets to fetch information about records.

I agree, labels and jackets do provide sufficient information, but dead wax contains much more. It contains information such as the catalog number, matrix number, symbols, etchings, and sometimes a locked-in groove with additional music information.

Out of all this information, the vinyl matrix is the most crucial one.

If you can read matrix codes, you can fetch information about manufacturing and mastering data of the record without reading information on labels or jackets.

Today, we will dive deeper into its concept, what information it can provide you, how to read it, and some interesting facts that you must know.

Let’s get started.

What is matrix number on vinyl records?

A matrix number, also known as the main number, is an alphanumeric code found on the dead wax or record label that provides information about the record.

It can be either stamped or handwritten on dead wax and printed on a record label.

In the early 1900s, it was introduced to identify different record size, side, and organization.

Since the mid-1900s, recording companies have started adding more letters, numbers, phrases/messages, and symbols that represent manufacturing and recording information.

What is its purpose?

Its purpose was to assign a number to each stamper, which further helps identify the stamper from which it’s pressed, records characteristics along with manufacturing and recording information.

This additional information helped in tracking inventory, managing the manufacturing process, ensuring quality, and proper labeling.

The most important part of the matrix code is the cut number. Along with these details, the disc cutting and mastering engineers also started stamping their names, logos, and special messages, giving each vinyl a unique identity.

Where to look to find the code:

The number can be found at two places:

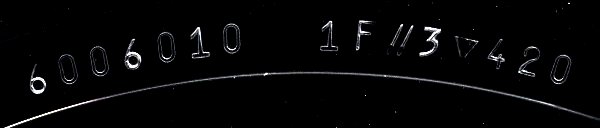

1) Dead wax

On run-out groove or dead wax, the main number is mostly found at the 6 o’clock position.

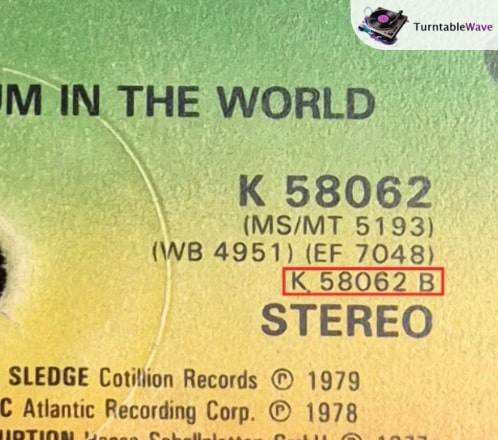

2) Record label

Now, let’s discuss the different types of information you can find through the number, along with code variations and etchings/markings.

Information that the matrix number can provide:

The combination of different characters, digits, and symbols can provide everything you want to know about your record.

There are many variations, and since it’s impossible to cover each, I will share some examples of a few record labels. Don’t worry, I have also shared a method below to find information about the main code of your vinyl record.

Let’s get started.

Pressing plants

Some combinations of characters represent the manufacturing plants in which a record is pressed.

In the past, sometimes the lacquer of a record was sent to different plants to press records at a faster pace. It’s quite understandable that each plant had its own equipment, which ultimately determines how the record sounds.

Some plants used to have advanced equipment, so records manufactured on that particular plant sound much better, which is why every collector has a list of favorite pressing plants.

Here are some variations to identify Columbia Records pressing plants:

- Bridgeport – ⦁, BP-#, CLB,

- Pitman- CP, P, PN, PXT, TP

- Santa Maria- CSM, CS, Ƨ, SM, CS, ϟ \, \ ϟ, S I, I S, SSSS, SXT

- Carrollton – GI,

- Hollywood- H, /// H, HH, H H

- Terre Haute- TH, CT, CTH, TXG, XTMR

- Chicago – C

Lacquer cut by/at or Mastered by/at

A lacquer is a blank aluminum disc used to create a stamper for a record. The stamper is further used to press vinyl records.

The “lacquer cut by” represents the disc cutting engineers who had signed the records with their unique characters, symbols, names, logos, or a combination of all these, and the “Lacquer cut at” represents the recording studio where it was cut.

Similarly, “mastered by” represents the mastering engineers who had signed the records with their unique characters, symbols, names, logos, or a combination of all these, and the “mastered at” represents the recording studio where it was mastered.

Although, both roles are different but can be done by a single person as well.

Here are a few examples of etching done by disc cutting or mastering engineers:

- George Peckham – Porky or A Porky Prime Cut

- Tony Taurins – Δ

- Alan Moy – ΔM

- Dave Moyssiadis – ΔM (2)

- Steve Smart – Oh (3)

- Rick O’Neil – ®

- Richard Finch – ® (2)

- Greg Calbi – ⚾

- Meredith Brooks – ♀

- Alexei Gottschau- Alexei, ANV

Here are a few examples of etching done by recording studios:

- CALYX – Calyx Mastering

- JLM – Joe Lambert Mastering

- GEARBOX- Gearbox Records

You might find the combination of both.

Let’s understand it by taking “CALYX Alexej” as an example.

Here, “CALYX” represents the name of the studio/plant where the lacquer was cut, i.e., Calyx Mastering. And, “Alexej” represents the name of the engineer who cut the Lacquer, i.e., Alexej Gottschau.

Year of pressing

The year of pressing is an important information that collectors look for when buying a record.

With this information alone, you can come way closer to determining whether the record is a first pressing or not.

Each manufacturer has adapted a different style to stamp the pressing year.

Here, we will take the RCA Victor record label style as an example.

| Code | Pressing Year |

| A0 to A9 | 1910 to 1919 |

| B0 to B9 | 1920 to 1929 |

| C0 to C9 | 1930 to 1939 |

| D0 to D9 | 1940 to 1949 |

| E0 to E4 | 1950 to 1954 |

| F | 1955 |

| G | 1956 |

| H | 1957 |

| J | 1958 |

| K | 1959 |

| L | 1960 |

| M | 1961 |

| N | 1962 |

| P | 1963 |

| R | 1964 |

| S | 1965 |

| T | 1966 |

| U | 1967 |

| W | 1968 |

| X | 1969 |

| Z | 1970 |

| A | 1971 |

| B | 1972 |

| C | 1973 |

| D | 1974 |

| E | 1975 |

| F | 1976 |

| G | 1977 |

| H | 1978 |

| J | 1979 |

| K | 1980 |

| L | 1981 |

| M | 1982 |

| N | 1983 |

| O | 1984 |

| P | 1985 |

| R | 1986 |

| S | 1987 |

Before 1954, the first character represented the decade and the second digit represented the year.

If your main code starts with “A5”, then “A” represents the decade, i.e., 1910s, and “5” represents the year, i.e., 1915.

After 1955, RCA Victor made some revisions, and since then, the first character has represented the year instead of decade.

Part, take, or cut number

You must have seen directors shouting cut while shooting a movie scene where they keeps repeating the process until they are satisfied with the cut.

Right?

The same concept is with vinyl records.

After lacquer is cut, 5-6 test copies are pressed. These copies are played on turntables to check for quality. If engineers found issues with the test pressings, they make required changes in the recordings and cut lacquer again but this time, a cut number is added to the lacquer’s matrix code.

There can be various other reasons behind a cut number being added to the code.

In the past, record stampers used to wear out after pressing a specific amount of records and to maintain the quality, a new stamper was made and a cut number was added to the main number.

Sometimes a record is pressed at different plants or countries where they have their own stampers so you may find different cut numbers depending on their actual manufacturing plant or country.

Most of the records have different variants in the market and collectors use these cut numbers to identify the first pressing.

Every record label has their own style to add cut numbers onto the record. Some adds it right after the code while some add it at 3 o’clock or 9 o’clock position on dead wax.

Different recording heads (acoustic or electrical recordings)

In the era of acoustic and electrical recordings, the manufacturing plants introduced a code that represented the mode of recording.

In the acoustic era, the grooves were engraved mechanically, i.e., an artist sang or played instruments in front of a gramophone’s or phonograph’s horn. Under the horn, a diaphragm was attached, which was further connected to the stylus.

When artists sang in front of a horn, the sound waves reached the diaphragm through the horn. The diaphragm responded to the amplified sound waves and vibrated. The stylus attached to the diaphragm vibrated, and it started engraving the grooves onto a phonograph record or a gramophone disc.

This was a mechanical way of sound recording. I recommend reading how does a phonograph works.

In 1925, electrical recording was introduced. Now, instead of using horns, a microphone was used. The process was similar to acoustic recording, but the horn was replaced with a microphone, and the groove-cutting head was replaced with an electric recording head. You can learn more about the recording process in different eras in this article.

After the introduction of electrical recording, manufacturers introduced new characters to the number.

The RCA Victor introduced “VE” to represent that the recording was done using the electrical recording head. Here are some examples: VE, BVE, BBVE, BCVE, PCVE, etc.

Different types of pressing

A vinyl record can have different type of pressing, such as special recordings, trail or test pressings, country-specific pressings and re-issues.

Each pressing has its own charactertics and historic reference making it an important metric for vinyl collectors.

Single-sided or double-sided records

Before 1950, some records used to have music only on one side.

To differentiate between the music and non-music sides, record labels, such as G&T, Pathé, Russell Hunting, Odeon, Edison Bell, HMV, COL, VIC, and Decca, added two alphabets that represented the record’s side.

- “SS” represented single-sided records.

- “DS” represented double-sided records.

Record size, speed & groove

In 1906, Victor introduced a character in the code that represented the record size, which was removed in 1909.

From 1906 to 1908, “A” represented 7-inch, “B” represented 10-inch, “C” represented 12-inch, “D” represented 14-inch, and “E” represented 8-inch. It was the fourth character in the code.

In the early 1920s, the label again started stamping similar characters, but this time they represented more than just record sizes. They represented speed, size, and groove (standard, transcription, mono, or stereo).

For example, from 1942 to 1954, the “A” character represented a 6½-inch size, 78 RPM speed, and groove type as standard, and the “B” represented a 10-inch size, 78 RPM speed, and groove type as standard. It was again in the fourth position in the code.

The list continues with some changes in information from 1955 to 1962 and from 1963 to 1990.

From 1963, the label split the size, speed, and groove into two parts: size/speed and groove type. The size/speed got third position, and the groove type got fourth position in the code.

If you have an RCA record manufactured between these years, you will see additional characters that tell you the record size, speed, and groove type.

Groove type: Mono, stereo, or quadraphonic

The mono record, also known as a monophonic record or monaural record, has only one audio channel for all music information. The sound will be the same on a single speaker or multiple speakers.

The stereo record, also known as a stereophonic record, has two or more audio channels. In simple words, the signals fetched by the stylus from the left channel are sent to the left speakers, and signals fetched from the right channel are sent to the right speakers. It’s just like listening to a live orchestra.

The quadraphonic record has four audio channels, and it requires special phono cartridges to fetch signals from all the channels.

To identify groove type, record labels introduced a character in the vinyl matrix code.

Let’s talk about the same example of RCA Victor records.

From 1963, the record label has rearranged the characters in the code. Now, record size and speed got third position, whereas groove type got fourth position in the code.

| Code | Groove type |

| A | Stereo |

| B | Mono (End) |

| C | Mono (Coarse) |

| G | Mono |

| H | Mono |

| M | Mono (End) |

| S | Stereo |

| T | Quadraphonic |

Record side

Knowing the record side was one of the main reasons why the vinyl matrix was introduced. There are two characters, “A” and “B”.

It is mostly added at the end, separated from the main number with a hyphen (-) or dash (—), where the “A” character represents Side A and “B” represents Side B.

Music Genre

The music genres of an album can be easily found on the record label and jacket.

Even some artists only release albums in specific genres but still, a character was introduced in the number.

The third character/digit of RCA Victor’s number represented the music genre/category, which was removed after 1963. After 1963, the third character started representing the size, speed, or master tape.

| Code | Category (Before 1955) | Category (1955-62) |

|---|---|---|

| A | Bluebird/Country & Western | – |

| B | Bluebird | – |

| C | Custom – Recorded by RCA | Children’s |

| D | Camden | – |

| AND | Educational | Educational |

| F | Foreign – Recorded in the U.S.A. | Slide Film – Frequency |

| G | – | Gramophone – Recorded in the U.K. |

| H | Groove label | – |

| J | Custom | R&B – Jazz |

| K | Custom – Tape furnished to RCA | – |

| L | Red Seal EP/ “X” label | – |

| M | V-Disc/Thesaurus | Transcription (Thesaurus) |

| N | – | Promotion & Premium |

| P | Victor (Popular) EP | Popular |

| Q | Custom – Lacquer furnished to RCA | Phonograph (also shown as 0) |

| R | Red Seal | Classical – Red Seal |

| S | Slide Film | Slide Film – Manual |

| T | V-Disc/Children’s | International – Recorded in the U.S.A. |

| In | Victor (Popular) | – |

| X | Foreign – Recorded outside the U.S.A. | – |

| IN | – | Country & Western |

| WITH | – | International – Recorded outside the U.S.A. |

Etchings – Unique messages

We already discussed that disc cutting and mastering engineers add their signature, logos and symbols on dead wax which is cool but, do you know many artists have added a unique message on dead wax?

If not, then get ready to know the most interesting thing about vinyl collecting. Many artists have added etchings which either represented themselves or some interesting facts about the album.

Here are some examples:

- The “Face Value” by Phil Collins has “Play Loud” etching.

- “A Blessed Unrest” by “The Parlour Trick” has “SOMETHING IS COMING” etching.

- “Dare To Be Stupid” by “Weird Al” has “More songs about television and food” etching.

These etchings make the vinyl collecting more interesting.

Interesting facts

There are some interesting facts that you must know:

Fact 1: Not always unique

Most people think that the matrix number is unique, but actually, it’s not. It is often found to be unique, but not always.

Fact 2: Both record sides have different numbers

Out of its original idea of introduction, identifying the record side is one of the major reasons.

While holding a vinyl record in your hand, you can’t tell the record’s side without looking at the label or the code.

It was a major problem and could cause manufacturers to press incorrect labels.

To solve this problem, one character, A or B, was added at the end of the main number, where “A” represents Side A and “B” represents Side B.

So, if your record’s matrix number is “X-5432-A”, it’s Side A, and if it’s “X-5432-B”, it’s Side B.

Fact 3: Used to find records worth by vinyl collectors

Although it’s intended to be used within different pressing plants, record collectors also study the matrix codes to know how rare their record collection is.

These metrics help them estimate the real worth of their vinyl collection.

Fact 4: Often mistaken with a catalogue number

Most of the time, the numeric digits in the main number and catalogue number are similar, which creates confusion among people, and they begin to represent the catalogue number as the main number.

The purpose of both is different.

The main number reveals information about the record itself, which might not be unique. However, the catalogue number is a unique identification number that contains alphanumeric digits, allowing record labels to control distribution, manage/track sales, and differentiate different releases.

To avoid confusion, the manufacturer prints the matrix upside down on the record label.

Source: Discogs